What’s the ask?

As part of our package of reforms to deliver a Safer World For All, we’re calling on the Australian government to increase investment in Australian aid.

Our specific asks are:

- Lifting Australia’s Official Development Assistance (ODA) to 0.37% of gross national income by 2027 with a bipartisan commitment to reach 0.5%.

- Doubling the Humanitarian Emergency Fund to $300 million annually for responding to new crises as they emerge.

- Investing an additional $350 million per year towards better preparing for mounting natural and humanitarian disasters, addressing protracted crises and preventing conflict overseas.

Official Development Assistance (ODA) refers to “government aid designed to promote the economic development and welfare of developing countries.”1 It is does not include funds donated by the public to non-government organisations, or funds provided by the private sector or philanthropic organisations.

Why these asks?

All around the world today, you will find people struggling to afford the basics to live let alone thrive and flourish. Every day, millions are hungry, drinking dirty water, living in inadequate shelter and unable to access healthcare or education. These problems interact and compound each other and result in a standard of living that is not equitable, nor sustainable.

While real progress had been made across the world on alleviating poverty, the COVID pandemic, a deluge in natural disasters (because of the changing climate) and an increase in conflict has meant that poverty levels are now rising again, for the first time in a generation.

“…the gap between acute need and global response capacity is widening.”

DFAT, New International Development policy, 2023

Right now, the gap between those who need assistance and the funding available for assistance (to address the ever-growing needs) is widening. In 2024, nearly 300 million people require humanitarian assistance and protection, an increase from 274 million at the beginning of 2022, yet global funding for humanitarian aid is falling short – by almost 50% – of what is needed.

When you are already vulnerable, your resilience and ability to recover becomes limited. We’re seeing this now as communities are finding it increasingly harder to recover when hit by a crisis, no matter how small or large. With an expected increase in the frequency and intensity of disasters (natural and manmade), without a concerted global effort those already vulnerable will be pushed to a point where recovery becomes even more challenging, if not impossible.

“The global humanitarian system is on the verge of collapse. Needs are rising. And funding is drying up. Our humanitarian operations are being forced to make massive cuts. But if we don’t feed the hungry, we are feeding conflict.”

UN Secretary-General António Guterres’ 2023 address in New York

We can solve this now.

There’s good news though, and that is that we can solve this. By increasing our ODA, we can invest in health, education, gender and disability equality, child development, livelihoods, social protection and stronger justice systems. We can also invest in disaster preparedness, protracted crises, conflict prevention and root causes. In so doing, we will effectively address both current issues and systemic problems, eradicating extreme poverty in the process.

In 2015 the world, including Australia, committed to eradicating extreme poverty by 2030 by agreeing to the Sustainable Development Goals. Part of this commitment included meeting the target of 0.7% of ODA/GNI.

We need to honour this commitment. All it will take is making the right choice and commit to doing the right thing. Increasing our investment in ODA is the right thing to do.

Meeting the Sustainable Development Goals, the Shared Blueprint for a Better Future

SDG 1

Target 1.1 By 2030, eradicate extreme poverty for all people everywhere, currently measured as people living on less than $1.25 a day

SDG 17

Target 17.2 Developed countries to implement fully their official development assistance commitments, including the commitment by many developed countries to achieve the target of 0.7 per cent of ODA/GNI to developing countries and 0.15 to 0.20 per cent of ODA/GNI to least developed countries; ODA providers are encouraged to consider setting a target to provide at least 0.20 per cent of ODA/GNI to least developed countries.

Can we afford it?

Often, the discussion around our ODA spend, particularly around calls to increase it, focus on this question: can we afford it? We think this question needs to be reframed. It’s not whether we can afford. It’s whether we can afford not to do this.

Australia is a wealthy nation. In fact, we are one of the wealthiest countries in the world yet our generosity as a nation is declining: right now, we are one of the least generous donors in the OCED, rated almost last on the OECD rankings for aid generosity (28th out of 31), despite being one of the richest.

Did you know?

The Australian Institute, 2023

“Australia is one of the wealthiest countries in the world. We have the 11th highest average income among the nations that make up the OECD, and we are the third richest country per adult in the world, behind only Switzerland and the US. Government debt is low by world standards – it sits at 70% of GDP, compared to the OECD average of 89 per cent”

What do we spend on aid?

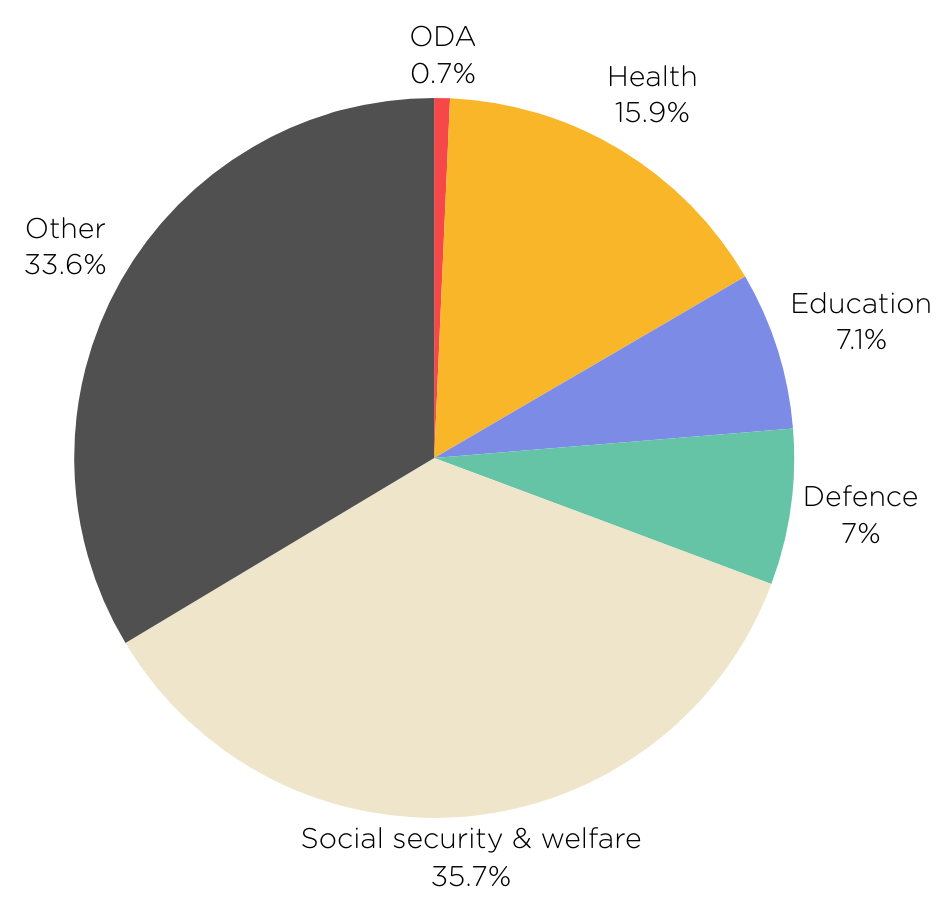

In the May 2023-24 Budget, spending on ODA comprised just 0.70% of the total government spend. Australia’s ODA as a percentage of GNI is currently at an all-time low, projected to be 0.19% for 2023-24, well below the current OECD average of 0.37%. And it is predicted to get even lower, ANU estimates that by 2026-27 ODA will be at 0.18%. By 2034-35, it will sit at only 0.14%.

Calculating ODA as a percentage of GNI – Gross National Income (GNI) is used as a comparison tool to assess and understand how much a country gives in aid (ODA) compared to the size of its economy (measured using GNI)

In 2023–24 the Australian Government will provide $4.77 billion in Official Development Assistance (ODA), whilst this may sound like a large figure, in reality ”our aid spending has typically accounted for around 1% of the Federal Budget. The percentage of aid from total Australian government spending has been on a downward trend since 2012-13, and is projected to be just 0.70% in 2023-24.”

DevPolicy: Aid Tracker, 2023

We can afford to be more generous

Increasing our spend on aid is not unreasonable or unobtainable but it does require a re-think about what we choose to spend on (a recalibration of sorts).

It also requires a recognition that if we’re really serious about eradicating poverty, (which we should be), and about using development cooperation as an essential tool for responding to global and regional challenges, then, just as we do in other areas of the economy, (i.e. the $130 billion for the JobKeeper subsidy in 2020) we have to be prepared to spend an amount that will actually make a difference.

As a comparison, other spends in the Australian federal budget are:

Just how much is $4.77 billion?

$4.77 billion equates to $190 per person per year on aid, an amount equivalent to 63 icecreams at the beach, or 38 takeaway coffees, or 34 pies at the football.

As a comparison, defence spending this year will exceed $50 billion for the first time.

Australians want to be generous

We see consistently across polls and surveys that being a responsible global citizen is what most Australians expect of Australia. The Lowy Institute found that:

- In 2022, Australians were overwhelmingly in favour of Australia providing foreign aid to Pacific Island states and almost all Australians (93%) were in favour of providing aid for disaster relief.

- In 2021, a growing majority of Australians – 60% – supported the federal government funding overseas aid.

- In 2022 four in ten (42%) say spending on foreign aid should be kept around current levels.

What meeting these asks will achieve

While increasing ODA demands a significant shift, the trajectory we are on – of increased poverty and instability – should be recognised as being unacceptable. If we are proactive, we can save millions of lives and trillions of dollars and insure ourselves against a future that we do not want and cannot afford.

Mateship, pitching in and helping-out are values that we all proudly see as Australian. In a globalised world these values also extend to people in other countries. Through an increased ODA budget we will make a significant difference in people’s lives. We will foster prosperity and stability across the globe and in our region. We will build a safer world for all.

Safer World for All campaign

This ask is part of a three-part transition plan, addressing immediate and urgent needs whilst also solving for the structural and systemic issues that underpin the way the world currently operates. The actions are: increase investment in Australian Aid; support a fairer global economy; and ensure a safer climate future. Taken together, these actions will create a safer world for all.